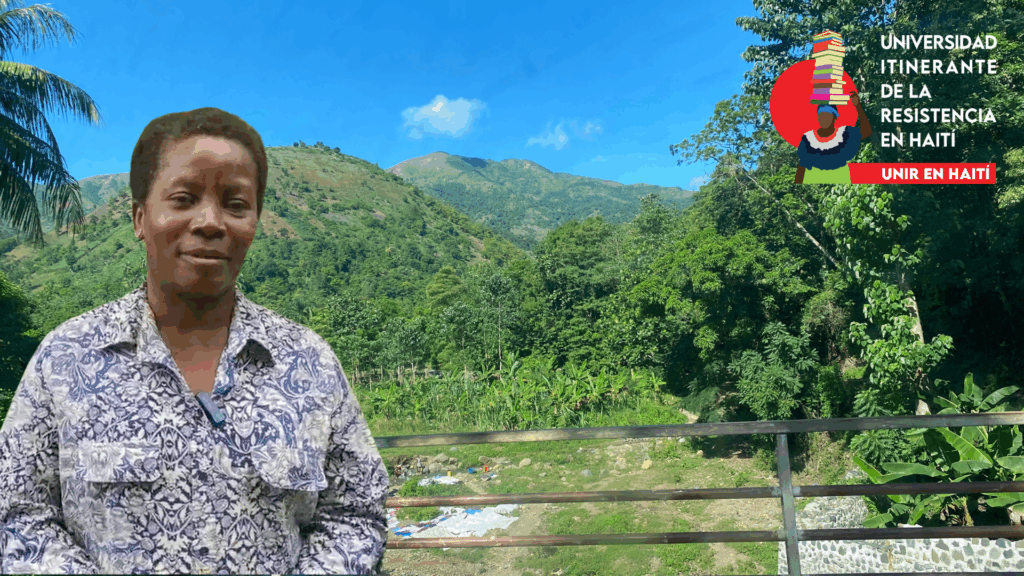

In northern Haiti, a female agronomist and community advocate is facing criminalization for caring for the land.

When the Caribbean sun begins to warm up Terrier-Rouge, in northeast Haiti, Joceline is already in the field. Her gait is firm, though fear has been her constant companion for months. She looks at the medicinal plants and says that each one has its own story. That the earth, like people, holds memory. Just a few weeks ago, that same land which always gave her strength also became the reason for her persecution.

On September 30th, she was arrested without a clear explanation. She spent ten days locked up, accused of a crime she never committed. “They told me it was by ‘superior order’,” she recounts. “But I know why it was: for defending what is ours.”

Joceline is an agronomist and a member of the organization Ti Plante and the UNIR-Haití community.

From this network, which promotes the defense of territory and food sovereignty, they articulate ties with social organizations throughout the entire Abya Yala.

Last December, her husband was the victim of an attempted murder. She managed to prevent it, but since then, she has lived under constant threat. The same aggressor, Sejour Rolinx, known as dòk, has persecuted and harassed her, and managed to have the authorities incarcerate her.

Disputed Lands

On October 1, 2025, one day after Joceline’s arrest, the Coordination of Resistance against Dappiyanp on Peasant Lands of the North and Northeast (KRDTPN-NE), a coalition of peasant organizations, sent a formal petition to the Departmental Director of the Northeast Anti-Corruption Unit (ULCC). In the letter, they denounced a network of illicit enrichment, misappropriation, and influence peddling linked to state lands.

According to the document, public officials, notaries, judges, and political figures participate in fraudulent operations in collusion with the Ministry of Economy and Finance, the Land Directorate, and local authorities. State lands in the Northeast department have become “the main source of corruption in the country.”

The conflict is not new. For over a decade, rural communities in the north have faced pressure from mining and agro-industrial projects. Beneath their soils lie reserves of gold, silver, copper, and bauxite—resources that awaken the interest of national and foreign companies. But this natural wealth has brought with it new forms of dispossession: evictions, judicial persecution, and violence against male and female leaders.

In theory, the Haitian Constitution guarantees farmers’ right of preference over state lands (Article 39) and the protection of private property (Article 36). In practice, these rights are violated daily.

Joceline and the Women Who Sow Resistance

Joceline is part of a generation of rural women and agronomists who sustain life on the margins of the State. They don’t just sow; they also organize, educate, and support. Their struggle is not just for a piece of land, but for the right to decide what happens on it.

“The land is not a business. It is what we are,” says Joceline. “We take care of the water, the seeds, the animals. That is also defending the country.”

Her case is not isolated. In different rural areas of the north and northeast, women territory defenders face criminalization, threats, and gender-based violence for their work. Many of them live without protection, but with a deep conviction: that the land cannot continue to be a source of profit and corruption.

From UNIR-Haití, we promote spaces for encounter and action with Haitian social organizations to strengthen the defense of the territory. Telling Joceline’s story is not only a denouncement: it is a way to protect her and to give visibility to many other women who face the same risk.